This has been discussed here before but that was some time back and it's good to revisit questions like this.B. wrote: ↑Sun Jul 23, 2023 9:34 am It's two different sources in the same report. The first part is from a newspaper article and the last part is from an informant. Who knows what the newspaper's sources were, but the CI didn't say anything here about Accardo losing his position that early.

It's possible though that issues started to develop in 1952 and were exaggerated by this article. One thing Accardo said on tape was that when he was boss he made a mistake and then his detractors started looking for him to make other mistakes. Maybe a series of issues took place in the years leading up to him stepping down even if it wasn't what was described in the 1954 article.

The FBI was, of course, noting that the information reported by CPD to the Tribune didn't match what their informant had told them. I don't recall seeing any later CI accounts, whether from members or associates, that discuss Accardo being forced out in either '52 or '54. As you noted, there was a 1960s FBI bug that captured an interesting conversation between Accardo and Gus Alex, where Accardo mentioned that he had fucked up, received a "slap", and then people were looking to give him another. Alex commented that Accardo had been "greedy" and acted like a "boob" during his time as boss.

We know from Bill Bonanno that Accardo was Chicago rappresentante as of the 1956 Commission meeting, as this was when Accardo formally announced that he was stepping down and introduced Giancana to the Commission as the new Chicago rappresentante. Bill was at the meeting and witnessed the proceedings as an aide to his father.

Now, from 1951 to 1954, Accardo indeed had a rough time. After having been subpoenaed to testify at the Kefauver Hearings, in 1951 Accardo was subpoenaed several times to appear before Chicago Grand Juries convened to investigate mob control over local LE, the black policy (numbers) racket, organized laborer, murders, etc. Despite the intense public scrutiny on him, Accardo decided that this was a good time to buy his 22-room mansion in River Forest, leading to newspaper and magazine articles discussing his power and opulent lifestyle. Accardo was arrested and held by CPD for questioning around this time, and then used a personal friend of his, Municipal Judge George Quillici, to get himself signed out of detention; naturally, this brought public calls to investigate mob influence in the local courts.

From the end of 1951 to early 1952, two big cases came down, leading to tons of press coverage, locally and nationally, and Grand Juries, etc.: the cigarette tax stamp ring (where outfit-linked tobacco distributors, including Chicago member Joe Fusco, used fake tax stamps to defraud the State of IL), and the horsemeat scandal (where outfit-controlled meat processing facilities swapped horse meat for ground beef, bribed State food inspection officials, and used counterfeit government inspection stamps). Both incidents brought major heat down on the mob and kept Accardo's name in the press spotlight. It was then reported by the Tribune in April 1952 that Ricca had taken Accardo down as "head of the syndicate" for his mishandling of these events.

In 1953, there were more Grand Juries, with local LE searching for Accardo to take him into custody for questioning (related to murders and other crimes). It was reported at this time that Accardo was flying into LA and Vegas and being turned away by local LE in those cities as an "undesirable".

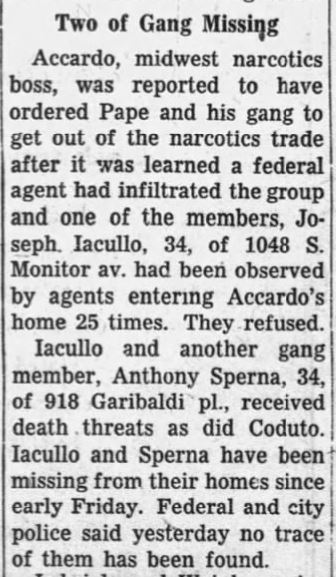

Then, in March of 1954, Accardo's next big "slap" came, when Federal narcotics agents busted a $10 mil-a-year heroin wholesaling ring under Tony Pape and Joe Iacullo. Iacullo was a personal associate of Accardo and it was revealed in the press that Iacullo had been surveilled by FBN agents meeting with Accardo in his mansion at least 25 times while they were tailing the leaders of the dope ring, and that FBN agents were tailing and surveilling Accardo as well. This led to Accardo being dubbed "The Narcotics Kingpin of the Midwest" in the press, which one can imagine was not a welcome characterization. Several members of the heroin ring wound up murdered, of course, but Accardo himself allegedly landed in hot water because of it, with the press reporting that a shot was fired above his head as a warning and that he had erected a new, taller, fence around his mansion. In April of 1954, Accardo applied for a passport, ostensibly for a fishing trip to South America, but Tribune sources instead believed that Accardo was attempting to flee the country as he feared being assassinated. The next month, Accardo withdrew his bid for the passport, after it was reported that he had been planning to fly to Chile and then take a second flight to Italy to meet with Charlie Lucky. Reporting declared a "feud" in the Chicago mafia, with a struggle between Accardo and Ricca for control. The bust of the heroin ring came less than two weeks after Ricca's parole term for the Hollywood Extortion case ended, with sources claiming that Ricca began "placing pressure on Accardo" at that point.

You can see here the kind of coverage that Accardo was getting at this time, from a May 1954 Tribune article discussing the murders of heroin ring members Pape and Frank "Shorty" Coduto:

In May of 1954, after withdrawing his application for the Chile passport, it was reported that Accardo was surveilled meeting with "Luciano spokesmen" Gaetano Ricci and Johnny Torrio at a Chicago hotel. After this, press coverage continued referring to Accardo as the head of the Chicago mafia "number 1 man in the syndicate", etc. Accardo seems to have basically officiated over Louie Campagna's 1955 funeral, as the Tribune reported that he held court for two days, and Ricca attended. Ricca also attended Accardo's annual July 4th party in 1955, where it was reported that Accardo shocked his 300+ guests by appearing in Bermuda shorts. Clearly, all the other stuff was one thing, but this was a bridge too far. Ricca obviously informed the Commission that a Don doesn't wear shorts, and by the next year, Accardo was forced to step down. Apart from committing sartorial nfamità, Accardo was also under investigation by the IRS at this time, following a case against him and Frank LaPorte for failing to pay taxes on the Owl Club in Calumet City, eventually leading to Accardo's 1960 conviction on tax evasion charges (overturned on appeal).